After an exciting last weekend in orbit, China’s first space station Tiangong 1 (Chinese for “celestial palace”) reentered Earth’s atmosphere early Monday morning on April 2nd at 00:16 Universal Time, give or take a minute, over the South Pacific.

The United States Strategic Command’s Joint Space Operations Center lists the reentry as occurring over latitude -14°S, longitude 164°W, 2,500 miles (4,000 km) south of Hawai’i and just over 300 miles east of American Samoa. The reentry occurred just before local noon.

The 8.5-ton, 34-foot long station was one of the largest objects to reenter in recent years, but it was by no means the largest ever: The reentry of 76-metric-ton Skylab in 1979, for example, was a media sensation. More recently, the 6-ton UARS satellite and the doomed Russian Mars mission Phobos-Grunt became reentry media celebs. Ironically, though the reentry of Tiangong-1 was uncontrolled and could have occurred anywhere from latitude 43N° to 43°S, it actually landed surprisingly close to Point Nemo — also known as the “satellite graveyard,” the favored location for satellite disposal.

The reentry seems to have gone unwitnessed by human eyes. No credible videos or images of the reentry have surfaced, though there’s always a chance that a wayward ship or aircraft might’ve been in visual range.

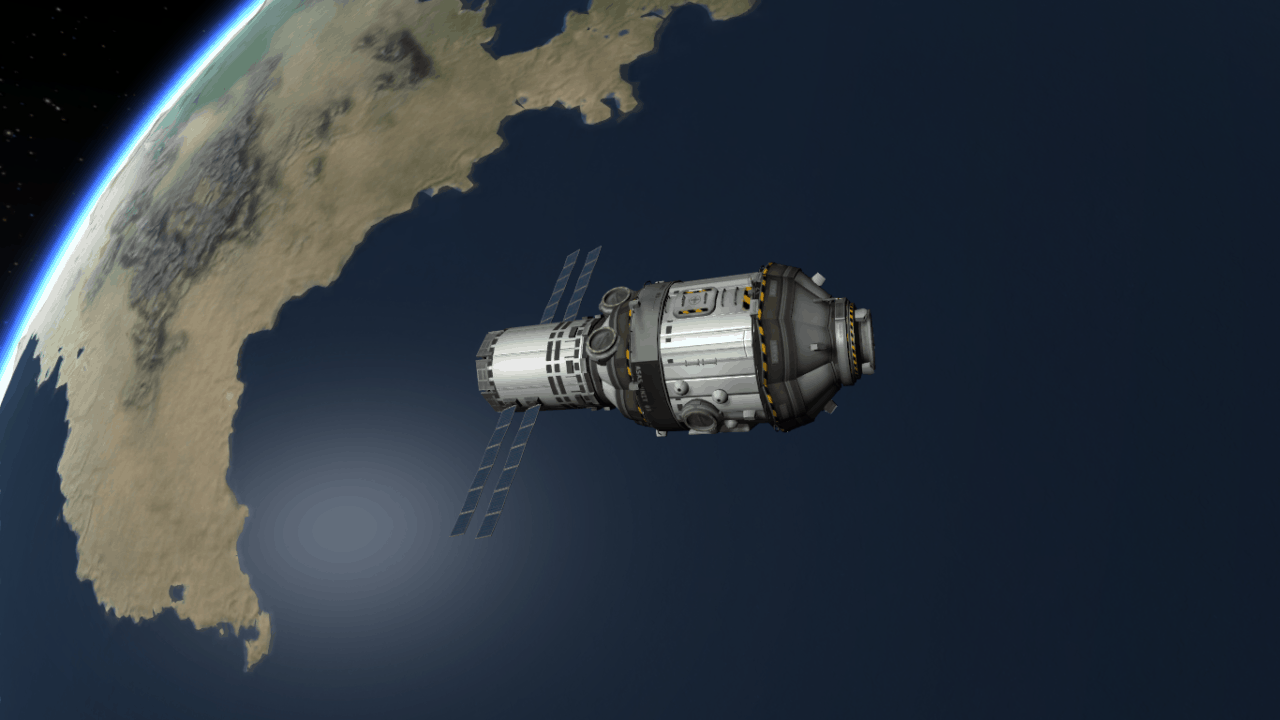

Launched on September 29, 2011, from the Jiuquan Space Center in China, school bus-sized Tiangong 1 was tiny in comparison to the massive International Space Station. In fact, there was always a minor debate as to whether the single-roomed module was really a space station, or just a docking target for China to practice automated cargo delivery and departure for a larger station. Two crewed missions delivered six Chinese astronauts to Tiangong 1 for two-week stays in 2012 and 2013.

Tiangong 1’s successor, Tiangong 2, was launched in 2016 and is still in orbit. China is often silent about their space exploration plans, so it’s unclear if they’ll revisit Tiangong 2 or when it would reenter. The Chinese Space Agency stated they would reenter Tiangong 1 after the final visit in 2013 . . . and then left it to reenter on its own nearly five years later.

Tiangong 1’s final passes were difficult to see this past weekend, though observers from New England to New Zealand did manage to catch some of its final passes before it met with fiery doom. I saw UARS a few years back on its final orbit, and can attest that it was a real fast mover compared to the ISS.

Predicting and Monitoring Reentry

NASA and the European Space Agency mounted a campaign to track the Chinese space station in an effort to better model future reentries. Unpredictable solar activity plays a key role, for example, in determining the height and density of Earth’s atmosphere, which drags on satellites in low-Earth orbit. An ebb in solar activity — such as we’re now in, as we head toward solar minimum in 2019-2020 — means less drag.

“The solar activity can influence the density of the upper atmosphere dramatically,” says Holger Krag (ESA-Space Debris Office). “One day we might be able to measure and predict the object’s behavior, but the prediction of the solar activity will always be difficult.”

n the last 48 hours prior to reentry, predictions crept back from mid-day of April 1st to early April 2nd, with the reentry location largely unknown. The station’s exact mass was another big unknown, as the “8.5 metric tons” often cited in the media assumes a ton of fuel still on board.

Public interest in the reentry spiked just before the weekend. We saw the usual carnival of “meteor wrongs” circulate around social media, including images purporting to be the Tiangong 1 reentry such as clips of the reentry of Mir, Hayabusa, and even screen captures from the movie Armageddon (!).

Arm-chair satellite sleuths also tried their hands at modeling the final reentry. It was interesting to see just how various tracking platforms, amateur and professional alike, stacked up against reality.

“This reentry was an interesting case, because it concerned an object with a larger mass than most reentries and included a few unknowns, most notably the exact mass of the station,” says Marco Langbroek (Leiden University, The Netherlands).

“What impressed me from monitoring this reentry,” Langbroek adds, “is how sensitive the time of reentry is to correct estimates of the influence of solar activity on the state of Earth’s thermosphere, as well as to correct estimates of the drag the spacecraft is experiencing.”

What’s next for China? Current International Traffic in Arms Regulations restrict NASA from exchanging technology with China, making China a conspicuously absent from the International Space Station program. Instead, China’s crewed space program is going it alone in low-Earth orbit. China plans to launch the core of its Tianhe 1 (“harmony in the heavens” in Chinese) modular space station next year.