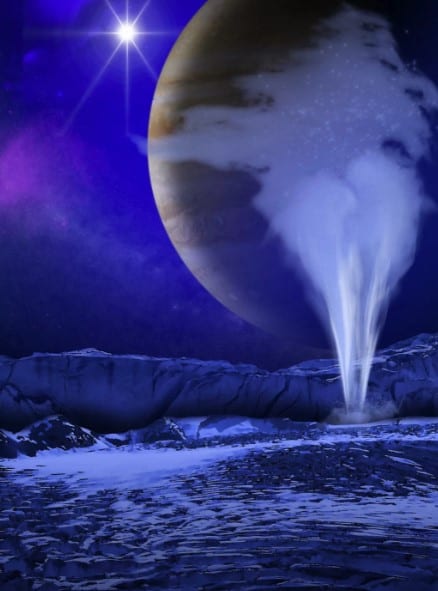

The case for a giant plume of water vapor wafting from Jupiter’s potentially life-supporting moon Europa just got a lot stronger.

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has spotted tantalizing signs of such a plume multiple times over the past half decade, but those measurements were near the limits of the powerful instrument’s sensitivity. Now, researchers report in a new study that NASA’s Galileo Jupiter probe, which orbited the planet from 1995 to 2003, also detected a likely Europa plume, during a close flyby of the icy moon in 1997.

The newly analyzed Galileo data provides “compelling independent evidence that there seems to be a plume on Europa,” said study lead author Xianzhe Jia, an associate professor in the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering at the University of Michigan.

This is exciting news for astrobiologists: If the plume is indeed real, it could offer a way for a spacecraft to sample Europa’s buried ocean of liquid water without even touching down on the moon. And NASA is working on a mission that could do just that.

Hints of a plume

At 1,900 miles (3,100 kilometers) wide, Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. But scientists think the Jovian satellite harbors a huge amount of liquid water — perhaps twice as much water as Earth does, in fact — in a deep global ocean sloshing beneath the object’s ice shell.

This ocean appears to be in contact with Europa’s rocky core, making possible a variety of interesting and complex chemical reactions. So, many astrobiologists regard Europa as one of the solar system’s best bets to host alien life, along with the icy Saturn moon Enceladus, which also features a subsurface ocean.

Near Enceladus’ south pole, more than 100 individual geysers continuously blast water ice, organic molecules and other material far out into space — so far that this plume stuff forms Saturn’s E ring. Researchers think the geyser material is coming from Enceladus’ ocean, so flying through the moon’s plume provides a possible way to search for signs of life on Enceladus without even touching down. (NASA’s Saturn-orbiting Cassini probe flew through Enceladus’ plume multiple times, but the spacecraft wasn’t equipped with life-detection gear. Nobody knew about Enceladus’ geysers until Cassini spotted them in 2005.)

Recently, evidence has been building that Europa may have a plume as well. In late 2012, Hubble spotted signs of such a feature near the moon’s south pole. Further Hubble observations in 2014 and 2016 identified candidate plumes close to Europa’s equator — in both cases, in the middle of a 200-mile-wide (320 km) Europan “hotspot” discovered by the Galileo probe.

As suggestive as these results were, they didn’t represent a definitive Europa plume discovery, researchers said at the time. That’s because project team members couldn’t conclusively rule out other possible explanations, such as instrument artifacts.

A new look at old data

The newly analyzed Galileo data could help solidify evidence for the plume’s existence.

During its time at Jupiter, Galileo performed 11 flybys of Europa. Jia and his team took an in-depth look at information the probe gathered during the closest of these encounters — a 1997 flyby that brought Galileo within 128 miles (206 km) of the moon’s frigid, fractured surface.

The researchers found that, during this flyby, Galileo detected a significant change in Europa’s magnetic field, as well as a brief but big increase in the density of plasma, or ionized gas. Both of these observations provide strong evidence of a plume, Jia said. And these lines of evidence are independent of those gathered by Hubble. For example, in the 2014 and 2016 candidate detections, the possible plumes blocked some ultraviolet light emitted by Jupiter.

Intriguingly, Jia and his colleagues also determined that the 1997 candidate plume emanated from the same general hotspot (or thermal anomaly) as the 2014 and 2016 phenomena.

Why did it take more than two decades to tease this result out of the Galileo data set? For starters, Jia said, the Galileo mission team wasn’t specifically looking for plumes.

In addition, “to make sense of the observations, we had to really go for sophisticated numerical modeling” techniques, he told Space.com. “And I don’t think those were available back 20 years ago.”

Flying through the plume?

The new study, which was published online today (May 14) in the journal Nature Astronomy, is undoubtedly of great interest to NASA. The agency is developing a $2 billion Jupiter-orbiting mission called Europa Clipper, which is scheduled to launch in the early to mid-2020s.

If all goes according to plan, Clipper will make 40 to 45 flybys of Europa over the course of its mission, studying the moon’s ice shell and subsurface ocean in an attempt to better understand Europa’s potential to host life as we know it. Europa Clipper will also scout out locations for a future lander mission, which Congress has directed the space agency to develop as well.

NASA officials have also said they’d like Clipper to dive through Europa’s putative plumes, if possible, to potentially grab fresh samples of the moon’s ocean (if plume material is indeed coming directly from that ocean).

The evidence gathered to date suggests that the processes producing Europa’s plumes — if they do indeed exist — may not be continuous like the geysers of Enceladus but instead intermittent. Ephemeral plumes could make it tough to plan sample-snagging flybys.

But the new results offer some optimism in this regard, Jia said. After all, scientists have now spotted possible plume activity in the same area of Europa multiple times over a 19-year span.

“The general region of the thermal anomaly might have long-lived plume activity,” Jia said.

Such activity may be caused by different individual jets or geysers turning on and off over time, he added. If NASA (and the rest of us who care about the search for alien life) get lucky, those jets may be on when the Europa Clipper reaches its destination and starts its science work.