Most Americans rely on Social Security benefits for income in retirement.

And one big question that plagues them is: Will those benefits be there for me when I need them?

The Social Security Board of Trustees said in April that its reserves will be depleted in 2035.

That means, if nothing is done up to that time, the system will only be able to pay 80% of expected benefits for retirees.

“The Trustees recommend that lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust to them,” Nancy A. Berryhill, acting commissioner of Social Security, said in a statement.

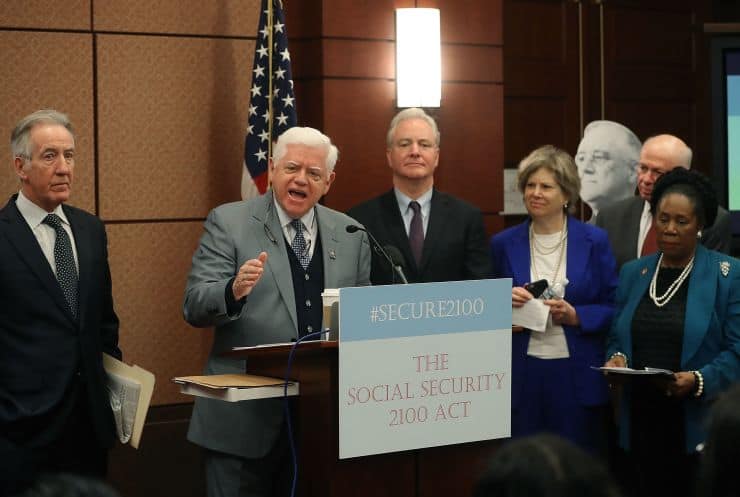

There are proposals to shore up the system, including the Social Security 2100 Act led by U.S. Rep. John Larson (D-Conn.).

“We’re going to do everything we can to continue to move this forward,” Larson said in an interview.

But some question whether Congress currently has the appetite to make the necessary changes.

That comes even as legislators could be poised to pass the most significant retirement reform legislation since 2006. That new law, known as the Secure Act, would change IRA distribution rules and make 401(k) plans more accessible for some American workers.

Proposed changes

The Social Security 2100 Act would extend the program’s solvency into the next century. Right now, the bill has more than 200 co-sponsors.

It is one of several proposals that have come up to address Social Security and Medicare in the past five years, according to Jamie Hopkins, director of retirement research at Carson Group.

“The Social Security 2100 Act is probably the only one that has garnered real attention and support,” Hopkins said.

The proposal would give those who are or will be receiving benefits a raise that is the equivalent of 2% of the average benefit. It would change the formula upon which annual cost-of-living adjustments are calculated, using instead the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly as a gauge for retirees’ expenses. It would also set the new minimum benefit at 25% above the poverty line.

The plan also would raise the limit for non-Social Security income before benefits begin to be taxed. The new limits would go to $50,000 for individuals and $100,000 for couples, up from the current $25,000 and $32,000 thresholds.

In order to pay for those changes, the bill calls for raising payroll taxes on wages over $400,000. Wages up to $132,900 are currently taxed.

It also calls for increased payroll contributions from workers and employers. That rate would increase to 7.4% from 6.2% and would be gradually phased in from 2020 to 2043. For the average worker, this would cost an estimated 50 cents more per week.

The plan has the support of Social Security reform advocates including the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare.

“We’ve really been supporters of many of the ideas that are incorporated in the bill for quite a long time,” said Max Richtman, the organization’s president and CEO.

Barriers to progress

The House Ways and Means Committee has held four hearings on Social Security so far. Once a full committee vote happens, it could move forward in the House.

“We’re hoping to have the full floor vote by the time we adjourn for the summer recess, which will allow people to be able to go back to their districts and talk about the Social Security plan,” Larson said.

From there, the issue would hopefully get picked up by the Senate.

Senators Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) are supporters. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) also put forward their own separate Social Security bill earlier this year.

“The questions remains will the president engage? I believe if he does there is a clear path forward to the passage of the bill,” Larson said. “If he doesn’t, I think this will be a major campaign issue.”

Hopkins said he sees a tough challenge for legislators who are trying to push these changes through. That is because there are not enough cuts to the system across the board, he said, such as benefit caps or tax reductions that would be necessary for Republican support.

“It could get passed through the House this year,” Hopkins said. “But it would, at least in the current make up, die in the Senate without some features being added to it.”

The other challenge is getting Congress to make the sweeping changes necessary, according to C. Eugene Steuerle, institute fellow and Richard B. Fisher chair at the Urban Institute.

For example, the Secure Act’s largest cost item is raising the age for required minimum distributions, which would eventually total roughly $1 billion per year, Steuerle said.

Social Security costs, meanwhile, are poised to increase by about $500 billion, from $1 trillion in 2019 to $1.5 trillion in 2029.

“Right now, there’s this refusal to address the issue as a whole,” Steuerle said. “It’s going to take a crisis. And even in a crisis, it’s going to take some leadership.”

‘Too big to fail’

That gets back to the question: Will Social Security benefits still be there for retirees?

The answer, experts said, is a definitive yes, though they will be reduced unless there is some kind of reform.

“Social Security and Medicare will be there, it’s just the promised growth rate in those systems is unsustainable,” Steuerle said.

For about one-third of retirees, Social Security represents their sole source of income. And for roughly two-thirds of retirees, Social Security represents more than half of their income.

“It would really be kind of devastating to the economy, the country, if Social Security were to just vanish, go away,” Hopkins said.

Social Security, one of the largest government expenditures year by year, is too big to fail, he said.

“It does need to be updated, but otherwise it functions extremely well,” Hopkins said. “It’s never missed a payment in its 80 years or so of existence.”