Now that the dust is starting to settle, what kind of report card does tax reform deserve?

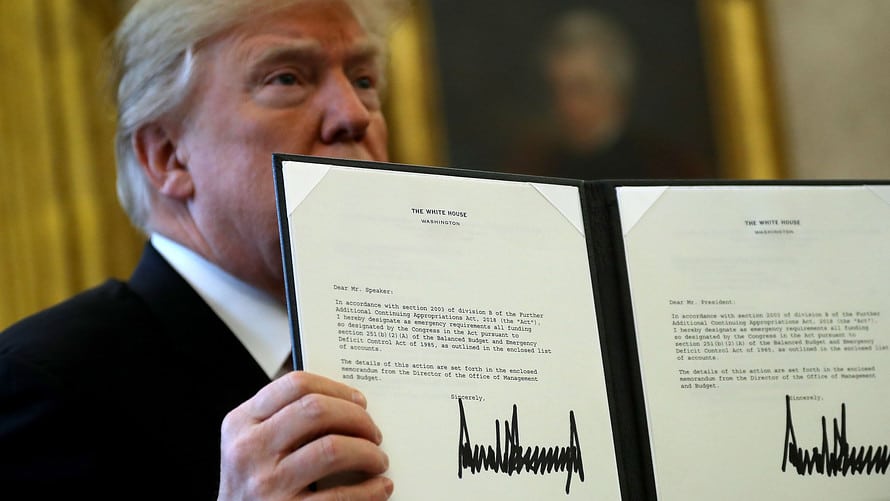

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, signed into law in December 2017, was widely considered to be one of the most impactful — and market friendly — pieces of legislation to be passed in several years. It sharply cut corporate tax rates and featured a plan to repatriate the untaxed profits of U.S. firms held overseas, two aims that Wall Street rallied in anticipation of. Both of these attributes, proponents argued, would lead to businesses ramping up their investments and fueling the next stage of growth by further boosting the already strong jobs market and lifting wages.

Since the passage, however, concerns about the economy’s prospects have grown rather than eased, and rather than spurring an acceleration in economic growth or hiring, many economic indicators have shown signs of slowing or stalling. U.S. GDP growth came in at 2.3% in the first quarter, below the 3% average of the previous three quarters as consumer spending hit its weakest level in five years. Recent data on the labor market showed fewer jobs created in April than had been expected, and 2018’s monthly average thus far is roughly in line with the average over recent years.

“To the extent we had exuberance about the tax bill between November and January, our view is now much more guarded. The biggest immediate impact is on earnings, but it’s important for us to see where the money is spent,” said Art Hogan, chief market strategist at Wunderlich Securities, referring to the repatriated cash. “We want to see a good balance that includes capital expenditures, not just buyback and dividends.”

Hogan, along with other analysts and market experts, agreed that too little time had passed since the bill’s passage to fairly analyze the impact it was having on the economy. However, they also said that anyone expecting an immediate spike in hiring or investments would’ve been disappointed.

“The place you’re seeing the impact show up the quickest is in stock buybacks, because that’s the easiest to do,” said JJ Kinahan, chief strategist at TD Ameritrade. “Longer term you’ll see companies make bigger investment plans, but that may not show up for three to six quarters. The impact of the law should be fine from that point of view; to the extent that companies reinvest, that should extend the bull market.”

Companies have been aggressively returning cash to shareholders since the bill’s passage. According to data from Goldman Sachs, companies in the S&P 500 have authorized $205 billion in buyback programs thus far this year, which represents growth of 48%. For the full year, the investment bank expects $650 billion to be spent on buybacks, up 23% from 2017. In addition, investors received a record $109.2 billion in dividend payouts in the first quarter; S&P Dow Jones Indices estimated that S&P components could spend as much as $1 trillion on buyback and dividend programs this year.

Among notable examples, Apple Inc. AAPL, +0.48% last week announced a $100 billion buyback program and raised its dividend by 16%.

Such programs can boost shareholder returns in the short term, however, they are not seen as having a significant direct impact on demand or broader economic growth.

Capital expenditures do contribute to growth, but the outlook on this front isn’t as rosy as the buyback picture. According to Credit Suisse, capex grew 20.1% in the first quarter of 2018, hitting an estimated $162 billion. However, the spending was highly concentrated: two internet companies accounted for one third of the growth, while just ten stocks made up two thirds of the total.

“It’s easy to attribute the recent increase to accelerated depreciation under the new tax plan, or the repatriation of overseas capital, but that would be a gross oversimplification,” wrote Jonathan Golub, the firm’s chief U.S. equity strategist.

Goldman Sachs forecast 2018 capex growth of 10%, or less than half the growth it expects in repurchasing programs.

Again, evaluating the law’s impact mere months after it was enacted may create a misleading picture. New York Fed President William Dudley said it would be “shocking” if the tax bill didn’t boost business spending, and that the only question was “how much” it would rise by. He added that it was too soon since the bill was passed for any pickup in investment to be seen in economic data.

“We’re expecting a 20-30% increase in capex, and some of that growth is being driven by the fiscal picture improving,” said Jeff Mills, co-chief investment strategist at PNC Financial Services Group. “However, some of it was going to happen anyway, and can’t be pegged to the tax bill.”

The Wells Fargo Investment Institute recently wrote that the U.S. economy was entering the late stage of its business cycle, but that “the passage of tax reform in December 2017 could help further extend the cycle’s life span.”

The lower tax rate did provide an immediate boost to corporate profits. Compared with the current profit growth rate of about 22%, Goldman estimated that growth would’ve been 9% had the bill not been passed. Results in the first quarter have been historically strong, but analysts aren’t wholly positive on the what the bill did to corporate America’s profit picture.

“The tax cut last year has created a lower quality increase in U.S. earnings growth that almost guarantees a peak rate of change by [the third quarter],” Morgan Stanley wrote. “Furthermore, the second order effects of said tax cuts are not all positive. Specifically, while an increase in capital spending and wages creates a revenue opportunity for some, it also creates higher costs for most. The net result is lower margins, particularly since the tax benefit is 100% ‘below the line.’”

Between Dec. 21, the last trading day before the tax bill was signed into law, and the close of trading on Monday, the S&P 500 SPX, -0.03% is down 0.6%. The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.01% is down 1.7% over that period, and the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, +0.02% is up 4.3%, thanks to outperformance in large-capitalization technology and internet names.

According to a survey of small business owners conducted by TD Bank, 48% of respondents said the tax bill wouldn’t benefit their businesses, while 20% actually cited it as their top obstacle for the year, second only to the 27% who cited “the health of the national economy.” While 22% of the small business owners polled plan to hire staff this year — compared with the 9% that did in 2017’s survey — even the bill’s supports indicated only a measured impact. Just 13% said they would purchase new equipment as a result of the bill.