An upgraded Northrop Grumman Antares rocket roared to life and vaulted into orbit Saturday for a flight to deliver 3.7 tons of crew supplies and equipment to the International Space Station. The Cygnus supply ship launched atop the Antares is carrying gear needed for up to five complex spacewalks to revive an ailing $2 billion particle physics experiment.

It is also carrying a wide variety of research hardware and experiment samples, 14 small satellites, and a prototype vest designed to shield astronauts on deep space missions from dangerous space radiation.

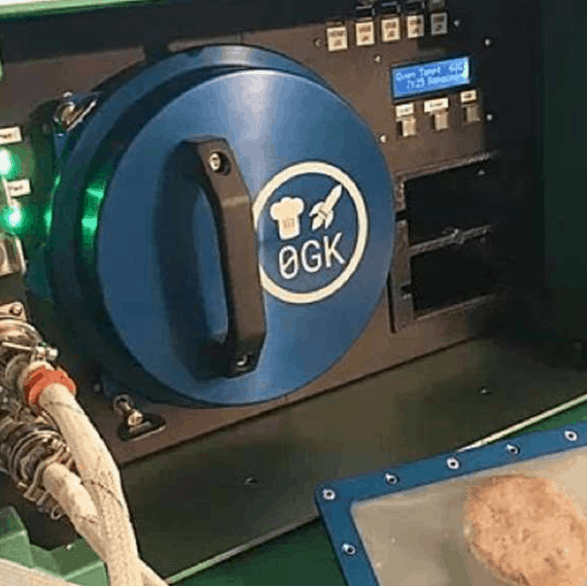

Also on board: a compact oven that will be used to bake the first cookies in orbit.

The stated goal is to find out whether baking is even possible in the weightless environment of space, looking ahead to eventual multi-year missions to Mars and beyond when astronauts will no doubt welcome more variety in their menus.

Only one cookie at a time can be baked in the compact oven, and no one knows what the chocolate chip treats will look like when they’re done. In the absence of gravity to hold a cookie on its baking sheet, the dough on board the station will be suspended in a special holder and mounted in the center of a cylindrical oven chamber.

“When you bake here on the ground, you put the cookie on the tray, the bottom is flat and the top is a little bit curved based on the ratio of your ingredients,” said Mary Murphy, an engineer with Nanoracks, which worked with Zero G Kitchen to develop the oven. “But obviously, nobody’s done this in space, so we don’t know exactly what it’s going to look like.”

“It could come out more like a cylinder, it could actually create a sphere. We really don’t know, and I think that’s one of the more exciting things we’ll find out.”

No matter what shape the morsels might take, the chance to bake up a batch of chocolate chip cookies – using dough provided by Hilton’s DoubleTree hotel chain – will be a clear treat for the space station’s six-member crew. They will be treated to the taste – and smell – of fresh-baked cookies.

“Everyone loves cookies,” said Murphy. “There are some preferences between types of cookies, but the vast majority of people, I think, are really on board with the chocolate chip.”

Liftoff on Saturday from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport at NASA’s Wallops Island, Virginia, flight facility came on time at 9:59:47 a.m. ET, the moment Earth’s rotation carried Virginia’s Easter Shore launch site into the plane of the station’s orbit.

Streaking away from pad 0A on a southeasterly trajectory, the Antares’ twin Russian-built RD-181 engines fired for about three minutes to boost the vehicle out of the thick lower atmosphere. A two-minute 43-second firing of the rocket’s solid-fuel upper stage propelled the Cygnus into a preliminary orbit about eight-and-a-half minutes after launch.

From there, the flight plan called for the unpiloted cargo ship to carry out an autonomous rendezvous with the space station, catching up early Monday and then standing by while astronaut Jessica Meir, operating the lab’s robot arm, locks onto a grapple fixture. From there, flight controllers operating the arm by remote control from Houston will pull the Cygnus in for berthing.

The mission is the 12th station resupply flight carried out by Northrop Grumman and the first under a new NASA contract calling for at least six flights through 2024.

To carry more cargo, the company beefed up the Antares first stage, allowing its engines to fire at full power throughout the climb to space instead of throttling back to reduce stress when powering through the regions of maximum atmospheric pressure.

Engineers also reduced the weight of both stages and increased the capacity of its Cygnus spacecraft. Additional storage lockers with power and cooling for active experiments were added and the capsule was modified to allow engineers to load short-shelf-life biological samples the day before launch.

A major objective of the latest flight is to deliver more than two dozen custom tools and a cooling pump module needed to extend the life of an instrument known as the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer. Mounted on the station’s solar power truss, the AMS is by far the most expensive single science experiment aboard the station and one of the most expensive ever launched.

Designed to operate for three years, the AMS, launched in 2011 on the next-to-last shuttle mission, has been capturing high-energy cosmic rays to help researchers resolve fundamental questions about the nature of anti-matter, the unseen “dark matter” that makes up most of the mass in the universe and the even-more-mysterious dark energy that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos.

In the eight years the AMS has been in operation, the instrument has captured more than 145 billion electrically charged cosmic ray particles shooting away from distant suns, stellar collisions, supernovas and other extreme energy events, detecting particles with energies as high as 3 trillion electron volts.

Such cosmic rays cannot be studied from the ground because they collide with atoms and molecules in Earth’s atmosphere, creating showers of secondary particles. The AMS is the most advanced cosmic ray detector ever placed in space and so far, the data it has collected does not fit accepted theory.

“The AMS results contradict cosmic ray theories and require the development of a comprehensive theory of the universe,” said Nobel Prize-winning physicist Sam Ting, the AMS principal investigator.

With a successful repair, he said, “AMS will continue to collect and analyze data for the lifetime of the space station. Whenever a precision instrument such as AMS is used to explore the unknown, new and exciting discoveries can be expected.”

But it will not be easy. Three of the four pumps needed to circulate carbon dioxide coolant through the AMS detector have failed, and the fourth is working intermittently.

To fix it, astronauts Drew Morgan and Luca Parmitano plan to carry out four and possibly five spacewalks, tentatively planned for Nov. 15, Nov. 22, Dec. 2, Dec. 7 and, if necessary, Dec. 11.

The repair work is especially challenging because the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer was not designed to be serviced in orbit. The overhaul will require the astronauts to cut and splice multiple coolant lines while plumbing in a new pump module. The spacewalks are considered the most complex since shuttle astronauts serviced the Hubble Space Telescope.

“We’ve been working for the last several years to put together a plan to go out and repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer,” said Kenny Todd, a senior space station manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. “It’s going to be a challenging set of spacewalks.”

Along with the AMS spacewalks, the station’s crew expects to welcome two more cargo ships before the end of the year – a SpaceX Dragon capsule on Dec. 6 and a Russian Progress on Dec. 22 – along with a visit by Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner.

Scheduled for launch Dec. 17 on an unpiloted test flight, the Starliner is expected to dock with the space station on Dec. 18, remain attached until Christmas Eve and then descend to a landing in the western United States.

Boeing and SpaceX, which already has carried out an unpiloted station docking with its Crew Dragon capsule, both plan to begin operational crew rotation flights in 2010, ending NASA’s sole reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft.