On Thursday, NASA’s inspector general released a report on the space agency’s commercial crew program, which seeks to pay Boeing and SpaceX to develop vehicles to transport astronauts to the International Space Station.

Although the report cites the usual technical issues that the companies are having with the development of their respective Starliner and Dragon spacecraft, far more illuminating is its discussion of costs. Notably, the report publishes estimated seat prices for the first time, and it also delves into the extent that Boeing has gone to extract more money from NASA above and beyond its fixed-price award.

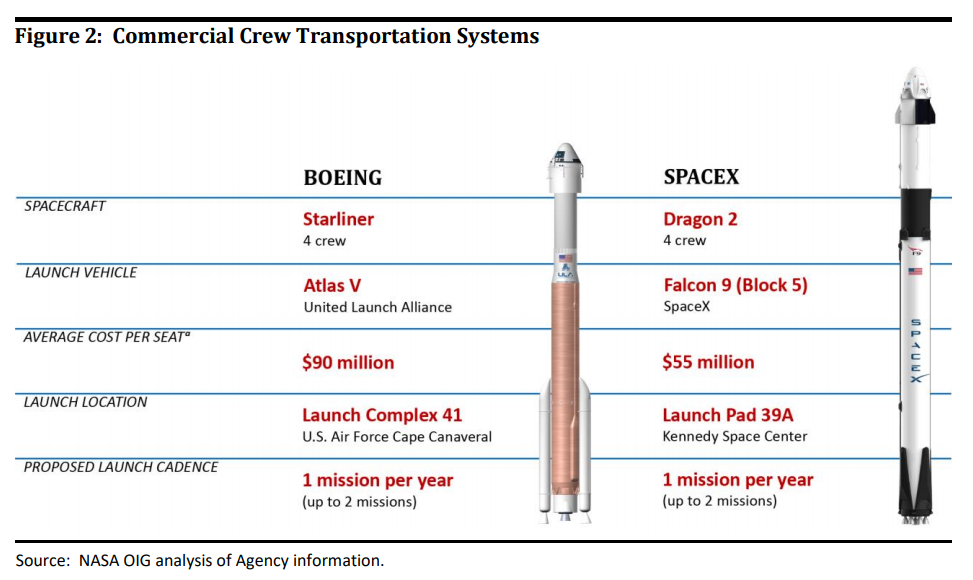

Boeing’s per-seat price already seemed like it would cost more than SpaceX. The company has received a total of $4.82 billion from NASA over the lifetime of the commercial crew program, compared to $3.14 billion for SpaceX. However, for the first time the government has published a per-seat price: $90 million for Starliner and $55 million for Dragon. Each capsule is expected to carry four astronauts to the space station during a nominal mission.

What is notable about Boeing’s price is that it is also higher than what NASA has paid the Russian space corporation, Roscosmos, for Soyuz spacecraft seats to fly US and partner-nation astronauts to the space station. Overall, NASA paid Russia an average cost per seat of $55.4 million for the 70 completed and planned missions from 2006 through 2020. Since 2017, NASA has paid an average of $79.7 million.

Beyond these seat prices, Inspector General Paul Martin’s report also notes that Boeing received additional funding from NASA, above and beyond its fixed-price award.

“Not consistent”

“We found that NASA agreed to pay an additional $287.2 million above Boeing’s fixed prices to mitigate a perceived 18-month gap in ISS flights anticipated in 2019 and to ensure the contractor continued as a second commercial crew provider, without offering similar opportunities to SpaceX,” the report states.

According to Martin, who had extensive access to NASA officials in the preparation of the report, Boeing in 2016 proposed pricing for its third through sixth crewed missions using the “single 2016 mission price,” which was substantially higher than NASA and Boeing had originally agreed upon. In response to this, NASA’s Office of Procurement determined this was “not consistent with the terms of the contract and did not match the contract’s fixed-price table.”

However, Boeing continued to press NASA for additional funding. After “prolonged negotiations,” according to Martin, Boeing offered some benefits to NASA, such as reduced lead times before the missions and a variable launch cadence. NASA then agreed to pay the additional $287.2 million for these four missions, which are likely to fly in the early 2020s.

Perhaps the most striking rationale for approving the additional funds was that Boeing may have discussed backing out of the commercial crew program (CCP). Martin writes, “According to several NASA officials, a significant consideration for paying Boeing such a premium was to ensure the contractor continued as a second crew transportation provider. CCP officials cited NASA’s guidance to maintain two US commercial crew providers to ensure redundancy in crew transportation as part of the rationale for approving the purchase of all four missions at higher prices.”

A spokesman for Boeing, Josh Barrett, denied that Boeing had threatened to end its commercial crew participation. “Boeing has made significant investments in the commercial crew program, and we are fully committed to flying the CST-100 Starliner and keeping the International Space Station fully crewed and operational,” he told Ars.

The report notes that as NASA was agreeing to pay Boeing extra for these benefits, a similar deal was not offered to SpaceX. “In contrast, SpaceX was not notified of this change in requirements and was not provided an opportunity to propose similar capabilities that could have resulted in less cost or broader mission flexibilities,” Martin writes.