If you’re eyeing your 401(k) account to help shore up your finances amid the coronavirus crisis, there are a couple of penalty-free ways you can do it if your employer allows it.

Just be sure you’re aware of the long-term implications. Each of the options available — a loan or withdrawal — would impact your balance in different ways down the road when you need that retirement money.

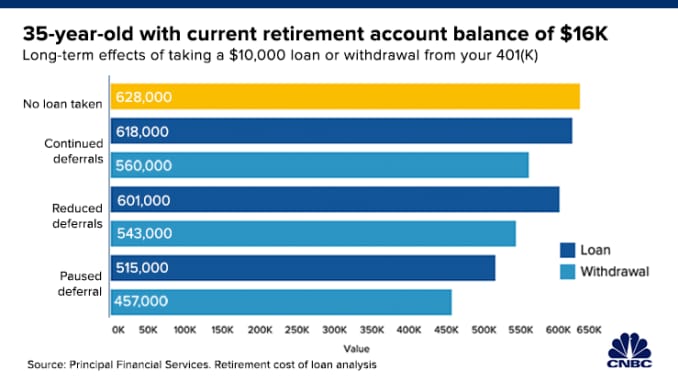

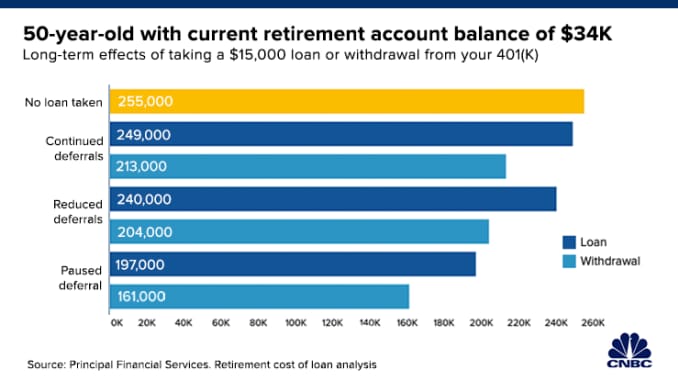

A recent report from Principal Financial Group includes an illustration of those long-term results. Depending on factors such as your age, whether contributions continue or are reduced or paused, and whether it’s a loan or withdrawal, the amount you potentially give up over time can amount to tens of thousands of dollars — if not well into six-figure territory.

“First and foremost, there are always going to be implications if you take from savings,” said certified financial planner Heather Winston, assistant director of financial planning and advice at Principal in Des Moines, Iowa. “The key is to make the most objective and pragmatic decision you can.”

Under the CARES Act, signed into law by President Donald Trump in late March, your employer can let you withdraw up to $100,000 for coronavirus-related reasons without the typical early withdrawal penalty if you’re under age 59½. You’d get three years to pay any taxes due or to replace the amount you removed.

Or, you can take a loan from your account of up to $100,000 (the usual limit is $50,000) and defer payments until next year. With this choice, you’re paying yourself back with interest, which is typically a percentage point or two above the prime rate. Be aware that while 401(k) loans usually are for five years, the balance typically becomes due if you leave your job before then and may end up counting as a distribution with taxes due.

The first chart below shows how a 35-year-old’s 401(k) balance would fare at age 65 based on several factors: whether a loan was taken or a withdrawal made, and whether contributions were paused or reduced for four years. The assumed annual return is 12% for the first three years (to account for higher gains after a recession) and 6% for the remaining years.

It also assumes the loan is repaid (with 4.5% interest over four years), as well as that the withdrawal is not replaced. Additionally, it uses a contribution rate of 6% of salary plus a 50% match from the employer. A 3% annual pay increase is also factored in, and 1% is used for a reduction in contributions (“reduced deferrals”).

This next chart uses the same assumptions for a 50-year-old and what their balance may look like at age 65.

If you’re considering a withdrawal or loan, Winston recommends first ensuring that you’ve exhausted other options that wouldn’t reduce your retirement savings. If there is no other option, she said, be sure to calculate accurately what the amount you remove from your account should be.

“Think through how much you might really need, not just what’s available to you,” Winston said. “You could take up to $100,000, but do you really need that?”

Additionally, she said that if you can afford to continue making contributions, it’s wise to do so.

“You want to avoid the double whammy of withdrawing and stopping deferring, whether it’s a loan or withdrawal,” Winston said.

Since the CARES Act went into effect in late March, Fidelity Investments has seen more than 370,000 individuals take a distribution from their retirement accounts. The average amount withdrawn was about $13,000; more than 8,500 people took $100,000.