Investors have spent much of the last year shrugging off geopolitical and economic risks, from the threat of nuclear conflict with North Korea to a potential trade war with China. Instead, they have focused on the strength of the United States economy, driven by banner corporate profits and President Trump’s push to lower taxes and reduce regulation.

The optimism helped lift stock markets ever higher, extending the boom into its ninth year.

Now, investors are suddenly skittish.

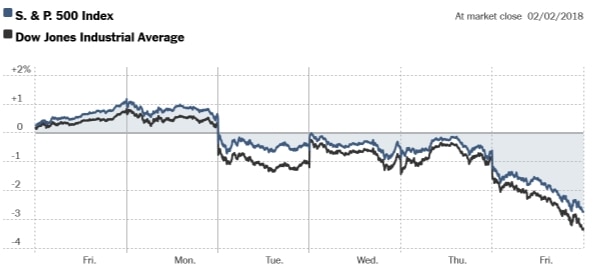

On Friday, stocks tumbled by more than 2 percent, propelling the market to its worst week in two years.

The immediate catalyst was the jobs report, which showed the strong United States economy might finally be translating into rising wages for American workers — a sign that higher inflation could be around the corner. But what is really worrying investors is that the fuel behind this stock market boom, namely cheap money from global central banks, may disappear sooner than they thought.

In recent weeks, the shift in sentiment has played out across the world’s largest financial markets. As stocks have sold off, Treasury yields have surged. The dollar has slumped.

“It’s a legitimate concern, when inflation spikes up a little bit, that people should evaluate how is this going to affect profits and how is this going to affect the Fed,” said Jonathan Golub, chief United States equity strategist at Credit Suisse. “The market is becoming more vigilant around these concerns, and that’s good and that’s healthy.”

In a strange way, investors are nervous that the global economy is doing too well.

Since stocks began climbing during the depths of the Great Recession in 2009, their rise has been supported by some of the lowest global interest rates seen since World War II. To jump-start growth, central bankers around the world slashed interest rates and took other steps to push down yields on safe government bonds.

Their goal was to incentivize investors to put their cash to work in the economy — for example, by buying corporate stocks and bonds — rather than stashing it in the relative safety of government bonds. The theory is that the fresh flood of capital would make it easier for companies to raise money, invest in their businesses and hire workers. Central banks wanted to heal their economies.

They have healed.

For the first time since the financial crisis of 2008, the world’s largest economies are growing in unison. The United States and China led the way, but the expansion now includes Europe, long mired in a debt crisis, and perennially laggard Japan.

Given the strength of the global economy, central banks, led by the United States Federal Reserve, have started to remove some of the supports that helped supercharge stock and bond prices over the last decade. The Fed started raising rates two years ago. And with the robust jobs report on Friday showing the fastest wage growth in years, some think the pace of rate increases could quicken.

Average hourly earnings for United States workers were 2.9 percent higher in January than the previous year, the fastest annual increase in years. Although a welcome development for workers, economists often view rising wages as an early indication of inflationary pressure. If faster price increases do begin to emerge, the Fed could try to head them off with more aggressive rate action.

The tenure of Janet L. Yellen, the Federal Reserve’s departing chairwoman who had her last working day on Friday, was characterized by a campaign to hold interest rates down. Her successor, Jerome H. Powell, will face different challenges as the Fed charts a new course in raising interest rates.

Interest rates that are set every day in the global bond markets are already leaping higher, in anticipation of central bank rate increases later this year. On Friday, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note — a widely used gauge for overall interest rates — rose to more than 2.8 percent, the highest level since early 2014.

Rising rates have myriad consequences, including making it more expensive for companies and individuals to borrow money, like for buying a home or a car. The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate is around 4.2 percent, up from less than 4 percent at the end of 2017.

Uncertainty about how the economy will react to rising borrowing costs has raised the blood pressure of investors. In one sign of a shift underway, a measure of expected market turbulence, the CBOE Volatility Index, jumped by more than 25 percent on Friday. The so-called VIX has spent months at historically low levels, reflecting a placid market mood that seems to have evaporated over the last week.

The stock markets this week have reflected the jitters.

The energy sector was especially hard hit, with energy giants ExxonMobil dropping 5.1 percent and Chevron falling 5.6 percent on Friday after reporting lackluster earnings. The energy sector of the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index fell 6.4 percent during the week, the biggest drop of all industrial sectors in the benchmark.

Health care stocks did not fare much better. Express Scripts, Cigna and UnitedHealth Group, among others, were battered Tuesday after Amazon, JPMorgan Chase and Berkshire Hathaway announced they were teaming up to create a health care company for their employees.

Tech stocks, which have been a crucial driver of the broader market rise, also slipped. Apple reported record-breaking profit late Thursday, but the company disappointed investors with a weaker-than-expected sales forecast. Its shares sank roughly 4.3 percent on Friday, worse than the broader market.

That is not to say the market is collapsing. The S.&P. 500 fell 3.9 percent this week. Still, it remains close to historic highs and 21 percent above where it stood a year ago, after another year of solid economic growth.

The United States economy expanded by a 2.6 percent annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2017. That is below the pace of some past expansions — the economy grew at around 4 percent annually in the late 1990s. But it is enough to keep creating significant numbers of jobs, including 200,000 in January.

The economic expansion should be a comfort to investors. Higher revenue allows companies to offset rising costs, such as workers’ pay, if inflation picks up. The tax cuts are also expected to help bolster growth.

“If we start to see growth slowing and inflation acceleration, that’s when I get concerned,” said Erin Browne, head of asset allocation at UBS Asset Management. “As long as growth continues to improve, a little bit more inflation that we’re seeing now is fine.”