Call it the quantum Garden of Eden. Fifty or so miles east of New York City, on the campus of Brookhaven National Laboratory, Eden Figueroa is one of the world’s pioneering gardeners planting the seeds of a quantum internet. Capable of sending enormous amounts of data over vast distances, it would work not just faster than the current internet but faster than the speed of light — instantaneously, in fact, like the teleportation of Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk in Star Trek.

Sitting in Brookhaven’s light-filled cafeteria, his shoulder-length black hair fighting to free itself from the clutches of a ponytail, Figueroa — a Mexico native who is an associate professor at Stony Brook University — tries to explain how it will work. He grabs hold of two plastic coffee cup lids, a saltshaker, a pepper shaker and a small cup of water, and begins moving them around on the lunch table like a magician with cards.

“I’m going to have a detector here and a detector here,” he says, pointing to the two lids. “Now there are many possibilities. Either those two go in here” — he points to the saltshaker — “or the two go in there,” nodding at the cup of water. “And then depending on what happened there, that will be the state,” he says, holding up the black pepper shaker, “that I’m preparing here.”

Got that? Me neither. But don’t worry. Only a few hundred or so physicists in the U.S., Europe and China really comprehend how to exploit some of the weirdest, most far-out aspects of quantum physics. In this strange arena, objects can exist in two or more states at the same time, called superpositions; they can interact with each other instantly over long distances; they can flash in and out of existence. Scientists like Figueroa want to harness that bizarre behavior and turn it into a functioning, new-age internet — one, they say, that will be ironclad for sending secure messages, impervious to hacking.

Already, Figueroa says his group has transmitted what he called “polarization states” between the Stony Brook and Brookhaven campuses using fiber infrastructure, adding up to 85 miles. Kerstin Kleese van Dam, director of Brookhaven Lab’s Computational Science Initiative, says it is “one of the largest quantum networks in the world, and the longest in the United States.”

Next, Figueroa hopes to teleport his quantum-based messages through the air, across Long Island Sound, to Yale University in Connecticut. Then he wants to go 50 miles east, using existing fiber-optic cables to connect with Long Island and Manhattan.

Kleese Van Dam says that although other groups in Europe and China have more funding and have been working much longer on the technology, in the U.S. “[Figueroa] is leading when it comes to having the knowledge and the equipment necessary to put together a quantum network in the next year or two.”

David Awschalom, a legend in the field who is a professor of spintronics and quantum information at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and director of the Chicago Quantum Exchange, calls Figueroa’s work “a fantastic project being done very thoughtfully and very well. I’m always cautious about saying something is the biggest or fastest,” he says. “It’s a worldwide effort right now in building prototype quantum networks as the next step toward building a quantum internet.” Other efforts to build quantum networks, he says, are underway in Japan, the U.K., the Netherlands and China — not to mention his own group’s project in Chicago.

U.S. efforts have lately been given a boost by the U.S. Department of Energy’s announcement in January that it would spend as much as $625 million to fund two to five quantum research centers. The move is part of the U.S. National Quantum Initiative signed into law by President Donald Trump on Dec. 21, 2018.

But what, really, is this thing called a quantum internet? How does it work? Figueroa, enraptured by his vision, told me of his plan with contagious enthusiasm, laughing sometimes as if it were all so simple that a child (or even an English major) could understand it. Not wanting to disappoint, I nodded my head and pretended that I knew what the hell he was talking about.

And, after spending two days with Figueroa last summer, following him around the campus of Brookhaven and the nearby Stony Brook, getting a firsthand look at his futuristic equipment, talking with other physicists around the world, reading a few books and perusing dozens of articles and studies, I began to kind of, sort of, get it. Not in all its unsettling depths, but in the general way that I understand how an internal-combustion engine goes vroom or why a toilet bowl flushes. And you can, too.

Untangling Entanglement

Leading me to the back room of his laboratory at Stony Brook, where he heads the quantum information technology group, Figueroa shows me a large table covered with a labyrinth of tiny mirrors, lasers and electronics. “This is where we create these photons that carry superpositions,” he says, “that then we can send into the fiber. OK? It’s very simple.”

Right.

Curiously, all the implications of the quantum internet can be traced back to an experiment so straightforward you can do it in your living room. Called the double slit experiment, it was first performed more than 200 years ago by British polymath Thomas Young.

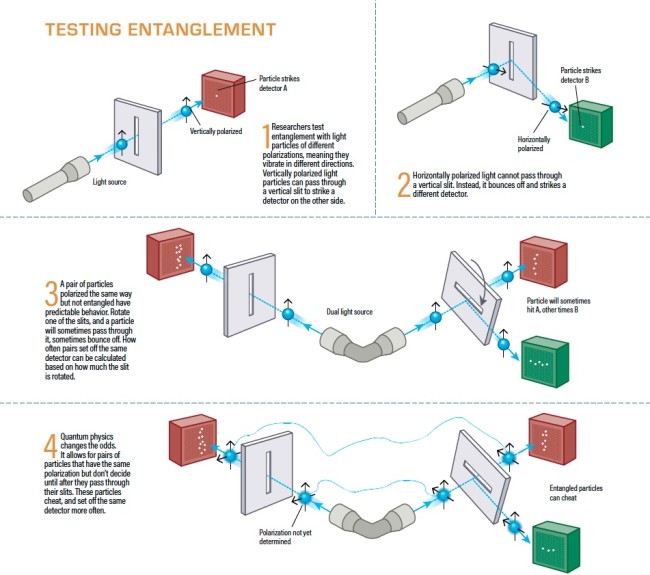

When shining a beam of light at a flat panel of material cut with two slits side-by-side, Young saw that the light passing through the slits created an interference pattern of dark and bright bands on a screen behind the panel. Only waves — light waves — emanating from the two slits could make such a pattern. Young concluded that Isaac Newton, who published a particle theory of light in 1704, was wrong. Light came in waves, not in particles.

But by the early 20th century, scientists had confirmed that light also came in particles — what physicist Gilbert N. Lewis called photons, or quanta. And incredibly, researchers found that even when single photons of light were sent flying one at a time at the double-slit panel, the interference pattern still appeared on the other side. Each particle, they realized, was also a wave, spread out like a schmear of cream cheese, and so traversed both slits simultaneously, thereby interfering with … itself on the other side.

Think on that. A single particle of light was in two places at once. That meant tickling a particle in one place should make it giggle in the other. Observing it in one place should reveal something about its twin. Erwin Schrödinger called the phenomenon entanglement — the very thing that Figueroa and other researchers are harnessing now to send information. Simply put, adding information, such as a message or data, to a particle in one location will make the data appear at the other location: the essence of teleportation.

But how, I ask Figueroa, do all these wild ideas work in practice, with nuts and bolts and physical devices?

“Let me show you where the magic happens,” he says.

Thanks for the Quantum Memories

“It’s just equipment and optics,” he tells me, pointing to an array of lasers and mirrors configured on a large table. “This is what people call Lego for adults.” On one end, a laser aims high-energy blue photons at a crystal, which breaks each one into a pair of lower-energy red photons; each of the two resulting red photons is now entangled with the other. Figueroa points out the path the photons take from mirror to mirror. “They do boop, boop, boop, boop, boop-boop-boop-boop. This is why we have this beautiful system. This is working, actually. This is beautiful,” he says.

Once entangled, one red photon is sent a short distance to a detector in Figueroa’s lab down the hall, while the other can be sent a dozen miles away to a detector at the Brookhaven National Lab. The differing distances would cause the two photons’ arrival times to fall slightly out of sync, which would disrupt their entanglement. To prevent that, Figueroa had to find a way to coordinate the arrival times of each down to the sub-nanosecond.about:blankabout:blank

But how? Other quantum labs freeze their stay-at-home photons to near-absolute zero as a way of tapping the brakes. Figueroa’s innovation, by contrast, works at room temperature: an inch-long glass tube containing a fog of trillions of rubidium atoms. That first morning when I visit Figueroa’s lab, he puts one of these tubes in my hand.

“What is it?” I ask him.

He smiles and says, “A quantum memory.”

Back when he was pursuing his doctorate at the University of Konstanz in Germany, Figueroa tells me, he had asked his professor if it would be possible to build a system that would work at room temperature without costly, complex freezers.

“I don’t think so,” he was told. “But prove me wrong.”

So, he did. By bouncing photons off a series of carefully placed mirrors and bombarding a mist of rubidium atoms with a network of lasers, Figueroa discovered that he could tune the wavelengths of entangled photons to broadcast a signal that electrons in the rubidium fog could receive. Voila! The entangled state of the photon is transferred, momentarily, into the entire cloud of atoms. A fraction of a nanosecond later, the entangled photon moves on, arriving at the detector at the same moment as its twin.

Incredibly, since completing his doctorate in 2012, igueroa has miniaturized the entire system for holding quantum memories into a portable device smaller than a carry-on suitcase, small enough to mount on an ordinary rack of computer servers at a data center — a crucial innovation if a quantum internet is ever to go mainstream. As his colleague and collaborator Dimitrios Katramatos tells me later that day: “They are portable, right? So, we loaded some of them up in a van one day and brought them from Stony Brook to Brookhaven.”

“He drove his wife’s van,” Figueroa says with a laugh. “Ever since we have called it the Quantum Van.”

Entanglement Swapping

Another problem remains, however — one that neither Figueroa nor Katramatos (nor any other quantum engineer in the world) has fully figured out so far: how to successfully transmit quantum-entangled photons via fiber-optic cables past a barrier that appears around the 60-mile mark. Beyond it, photons unintentionally interact with the cable, its housing or even sunlight from above-ground, thereby destroying its entanglement.

The proposed solution, Figueroa explains, is something called “entanglement swapping.” And quantum engineers around the world are competing to apply the concept to a working prototype.

“The idea has by now been around for 20 years,” says Mikhail Lukin, a leading quantum theoretician and experimentalist at Harvard University. “Up to now, no one has succeeded in building one capable of being used in a practical application. As far as I understand, that’s what [Figueroa]’s group is trying to do.”

To explain his plan, Figueroa leads me into a small meeting room, where he has it all mapped out on a whiteboard.

“Let me show you something really cool,” he says.

Instead of creating only one pair of entangled photons and trying to send it to a lab 100 miles away, he explains, a second set of entangled pairs are created in two different substations located at the 25-mile and 75-mile marks. These substations will shoot one photon of the pair toward each other and the other toward the closest of the two labs. When one photon from each of the two pairs meets at the 50-mile mark, they will become entangled, automatically entangling the other remaining photons in the distant laboratories. Once this entanglement has been shared, the information Figueroa wanted to send can be teleported to the lab 100 miles away, overcoming the barrier.

“You see?” he says with charming enthusiasm. “Easy.”

The Quantum Future

And what about teleporting not just information, not just messages, but also particles, molecules, cells or Captain Kirk? When the first experimental demonstration of entanglement was reported in December 1997, IBM physicist Charles H. Bennett told The New York Times: “It would be utterly infeasible to do it even on something as small as a bacterium.” (Bennett, it should be pointed out, had coined the term quantum teleportation four years earlier, so you would think he would be correct.)

But 21 years later, in the fall of 2018, Oxford University researchers reported exactly what Bennett had said was “utterly infeasible”: the entanglement of a living bacterium with a photon of light. Not all physicists were persuaded by the findings, however, based as they were on the Oxford team’s analysis of another group’s experiment. But then, nobody knows how far the quantum revolution will go — certainly not Figueroa.

“Many of the things these devices will do, we are still trying to figure it out,” he tells me. “At the moment, we are just trying to create technology that works. The really far reaches of what is possible are still to be discovered.”

Before leaving him, I ask Figueroa how his friends, family and neighbors try to understand his cryptic work. He tells me a story about his father-in-law. Back when Figueroa was conducting postdoctoral research in Germany, his wife’s father came to visit. After giving him a two-hour tour of the lab, Figueroa asked him what he thought of it all.

“I didn’t understand a word you said in there,” his father-in-law said, “but I know it’s the most amazing thing I have ever seen.”

I could empathize. That’s how I felt before visiting Figueroa, interrogating him repeatedly over the phone, and reading his papers with far-out titles like “A Single-Atom Quantum Memory” and “Quantum Memory for Squeezed Light.” But after all that, the whole thing began to make sense to me. And I hope it does now for you, too.

Kind of.