Software has been a crucial component to all of NASA’s major achievements, from space travel to the deepest images of our universe. Naturally, NASA’s need for high-quality scientific software has led it to open source developers, and now to an ambitious new program based on the larger principles of “open science.”

Bringing NASA’s open source message to the annual FOSDEM conference was Steve Crawford, a space-loving astronomer who is now also the data officer of NASA’s science directorate, the group engaging the scientific community to define questions and expand research.

Previously Crawford managed the team building the calibration software for the Webb Space Telescope, and Crawford joked that the organizers said his talk sound like “an upbeat, great way to end the meeting with lots of pretty pictures.”

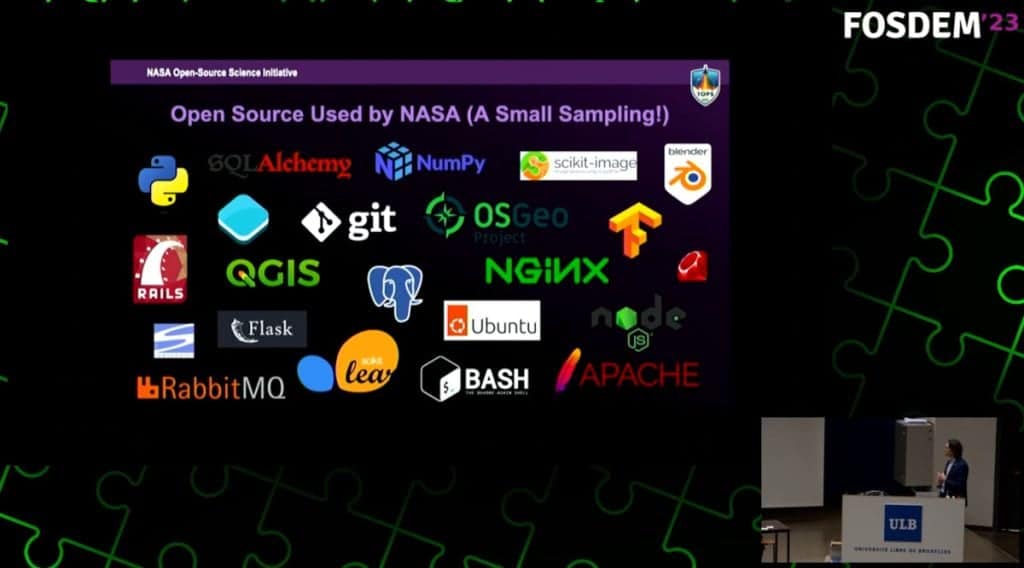

Crawford delivered a wide-ranging presentation that began by noting that from planet-monitoring databases to mission-running software, “Open Source Software is critical to addressing NASA’s biggest challenges on climate change, exploring the solar system, and discovering life beyond Earth.”

For a success story, Crawford pointed to the Mars Ingenuity helicopter, successfully delivered to Mars in 2021 and performing the first flight of a human object in an atmosphere besides Earth. “We’re actually flying a copter on another planet.” Though it was expected to make just five flights, it’s now completed more than 40, and “It’s still flying — it’s still exploring!”

But more importantly, it’s guided by open source flight-control software — the F Prime software released in 2017 by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. To celebrate, NASA and JPL partnered with GitHub to recognize all the many software contributors — over 12,000 of them — with a “Mars 2020 Helicopter Contributor” badge on their GitHub profile.

And even the James Webb Space Telescope — a project first conceived in the 1990s — involved open source software. The telescope’s pre-launch testing for processes and software relied on publicly-available calibration code based on Python’s NumPy library.

But Crawford then explained that NASA and the people working at NASA also release “a huge amount” of open source software, including “a wide range of different projects touching on both planetary science, astronomy, heliophysics, earth science, along with technology development and other aspects.”

One example is the cloud-computing platform OpenStack, which traces its origins to internal platforms at both NASA and RackSpace. “We still use this in our ADAPT supercomputer center and for our on-premise cloud computing… But with RackSpace we’ve handed this over to the wider community for further development.”

Crawford also reminded the audience of code.nasa.gov, its repository for NASA’s open source software, currently featuring over 500 officially-released projects. But there’s now also the just-released Science Discovery Engine, “a system to explore all of our datasets, software, and technical documents across all of the science mission directorate.”

Crawford estimates over 44,000 pieces of software has been released by different NASA researchers and missions.

Besides NASA’s GitHub repository, Crawford noted there’s separate repositories for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Space Telescope Scientific Institute. Also online is the NASA software catalog (“hundreds of new software programs you can download for free to use in a wide variety of technical applications,” boasts its home page). There’s even the Astrophysics Data System, an indexed and searchable collection of more than 15 million abstracts and full texts of major astronomy and physics publications.

Giving Back

Crawford turned to another NASA-originating software program NASTRAN, a finite element analysis program developed in the 1960s and released into the public domain in the 1970s, and JPL Spice Toolkit, which Crawford calls “the software you use if you want to know where a comet or an asteroid that you want to land on will be in 10 years.” The Spice took kit led to a Python wrapper called SpiceyPy (created by college undergraduate Andrew Annex) that’s now used in a wide range of space agency missions.

Crawford called the software an open source success story — Annex continued developing it in his spare time — but also an examples of the challenges projects face. “A lot of our open source systems do actually depend on a small number of developers who are actually maintaining it and keeping the code active and working,” Crawford pointed out, referring to the classic XKCD comic on sustainability.

To help the situation, NASA’s science directorate is now funding open source software, especially science-related projects. In the last two years, it provided $3 million in financial support to 22 different open source projects.

But beyond that, NASA has also embraced a wider open philosophy. Last month a new official policy on scientific information was released by NASA’s science directorate. “We want to make things as open as possible, as restricted as necessary, and always secure,” Crawford said.

This means no “embargo” period when research and publications can’t be shared with the general public — with supporting research data and software also shared at the time of publication. Even mission data will be released as soon as possible and made available without restrictions — and mission software is developed out in the open.

Crawford calls this a lesson they learned from the James Webb Space Telescope: “having that software available for everyone to actually be able to both have access to it and also reuse it — improves how science is done.” Going forward they plan to release data and software under permissive use licenses like Creative Commons Zero.

And finally, the new policy encourages NASA employees to use and contribute to Open Source projects.

But there’s also an outreach to the world beyond NASA — including a new $40 million, five-year program called Transform to Open Science. The idea of open science involves free availability of research information to encourage outside contributions, and NASA is actively trying to lead us there.

The official TOPS webpage calls it NASA’s “global community initiative to spark change and inspire open science engagement through events and activities that will shift the current paradigm.” Throughout 2023, NASA TOPS will be partnering with 12 scientific professional societies in the scientific community “to advance the adoption of open science, roll out an open science curriculum, and support minority-serving institutions engagement with NASA through prizes, challenges, and hackathons.”

An announcement at WhiteHouse.gov promises the broader federal program will include “new curricula in open science for students, researchers, and the public, as well as robust engagement with people and groups that have been historically underrepresented in science, conferences on open science throughout the year, and other new initiatives.”

NASA’s commitment to openness keeps spreading. One of the directorate’s most important work is its study of climate change’s impact, and Crawford reminded the audience that they make all their data open — over 70PB available in the cloud through open APIs, and even more in different systems “that are open for you to use in any way that you like to help address these questions.”

There are many different projects, including the environment-focused Prediction Of Worldwide Energy Resources (or POWER). But the ultimate goal is always empowering the broader open source community “to actually develop the apps, to build the open source tools on top of this, to actually use it in different ways… to actually answer some of the toughest questions that we have around climate change and our environment.”

And now with Japan and Europe’s space agency, NASA is working on the Earth System Observatory to provide “even a closer view of climate effects on earth.” There’ll be 600PB of data — “all freely available and accessible to the world, to be able to access it and look at it and build things on it…”

Crawford says NASA’s own goals for its transformation program include training 20,000 researchers — which can earn them a NASA “open science” badge — in a program that includes lessons on open sourcing software.

“We’re also following our own advice here. Everything that we’re doing with this project is going to be open sourced, on GitHub, so that community members can contribute to it.” Other goals include doubling the participation of historically excluded groups — and enabling five major scientific discoveries that happen with open science principles.

And Crawford shared a hope that FOSDEM attendees would also “take steps forward to make your science and your results more open as well.”