How do you spot a truly independent financial adviser? Well, it’s tricky. The $4.6 billion financial planning industry is characterised by a complex web of allegiances and opaque reward structures that, as the Hayne royal commission has demonstrated, do not always serve the best interests of consumers.

While it is impossible to guard against fibs – yes, the commission has heard about planners misrepresenting about their qualifications – there are a few basic checks and precautions you can take.

First some context. Back in 2009, when former Labor MP Bernie Ripoll chaired a landmark inquiry into the financial planning industry, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) described the typical financial planner as playing a dual role of providing advice for clients and acting as “the sales force for financial product manufacturers”.

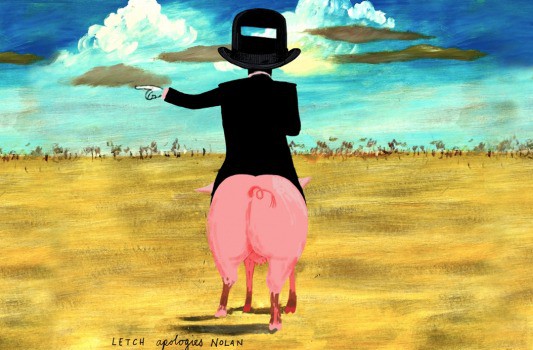

Financial products are things like superannuation, insurance and loans, and the manufacturers are typically banks and other financial institutions. It is this dual role – turbocharged by sales incentives and commissions – identified by ASIC which has given rise to the conflicted advice tsunami that has beset the industry.

The Future of Financial Advice reforms were meant to remedy the situation, and they did introduce a legal requirement for advisers to act in the best interests of their clients (as opposed to themselves or a product manufacturer) and bans on certain types of commissions. Since July 1, 2013, financial advisers have been prohibited from receiving particular benefits known as conflicted remuneration (where their potential to benefit influences their advice).

But as the Hayne royal commission has demonstrated, problems persist.

“Members of the public are concerned that financial advisers are often only recommending particular in-house or commissioned products,” senior counsel assisting the royal commission Rowena Orr said last week. “A number of submissions refer to financial advisers engaging in improper conduct in order to drive greater investment – in particular, inhouse products.”

ASIC register

A background briefing at the royal commission says a financial planner or adviser is a “person or authorised representative of an organisation licensed by ASIC to provide advice on some or all of these areas: investing superannuation, retirement planning, estate planning, insurance and taxation”. From January 1, 2019, there will be restrictions on who can call themselves a “financial planner” or “financial adviser”. As of April 1, 2018, there were 25,386 financial advisers registered in Australia.

When selecting a financial adviser, the number one check to undertake is a search of the ASIC register of financial advisers. The register was launched in 2015 and provides qualifications, training and members of industry and professional bodies. It also lists any banning orders or disqualifications made against a financial adviser, as well as any enforceable undertakings agreed to with ASIC.

Qualifications are important although, as the commission has heard, not everybody tells the truth. Tougher education standards are in the pipeline, but for now the minimum requirement for financial planners and self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF) advisers is known as RG 146. It is a very basic course and has been highly criticised for being low cost and able to be completed within days.

While it sounds like a no-brainer, look for higher qualifications such as a diploma, advanced diploma or bachelor degree qualification in disciplines such as finance, economics, accounting or financial planning itself. As ASIC’s Smart Money website notes, some lawyers offer financial services as well as legal advice. “If a lawyer is giving you personal financial advice, they must have an AFS [Australian financial services] licence or work for someone that holds an AFS licence,” it says.

Consumer group Choice says that, at a minimum, financial advisers must provide responses in relation to the following three points:

- ull disclosure of which financial institutions the adviser has a financial relationship with, if any.

- An explanation of why the adviser is recommending products through which they receive a commission, if applicable. They may still be valid recommendations, but the adviser should be able to clearly explain (and in fact is required by law to be able to justify) why the advice suits your circumstances.

- An annual statement of advice (SOA), why it was given and how much it would cost if the adviser charges on an ongoing instead of fee-for-service basis.

Types of products

Further, where a financial adviser provides personal advice, they must supply a financial services guide which sets out information such as how the planner is to be paid and the types of products he or she is licensed to offer.

Says Choice: “Advisers shouldn’t be recommending products and strategies that earn them high commissions; they should be making recommendations based on your best interests. End of story.”

As evidenced in hearings of the royal commission, consumers should be wary of aggressive pushing of certain types of products, such as self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs). SMSFs can be costly to run and eagerness to set them up can emanate from firms and individuals who earn tidy management fees.

The commission heard from nurse Jacqueline McDowall, who was falsely led to believe she and husband Hugh could borrow as much as $2 million to buy a bed-and-breakfast business if they set up an SMSF. They established the SMSF, at considerable cost, only to find there was no prospect they could borrow anything like that amount.

Another woman, Donna McKenna, told the commission she was advised to roll her existing superannuation benefits into an SMSF so she could buy an investment property. Had she taken the advice of Sam Henderson, she would have lost $500,000 in benefits in her old fund. McKenna told the commission the advice was laughable. “I thought if I went to an independently owned financial planning firm that I wouldn’t be subjected to the product flogging of the type associated with the big banks, and yet all I’m being flogged is Henderson Maxwell’s own products and services,” she said. “I all but threw the advice in the bin at that stage.”

Membership of an industry group should be a harbinger of high standards, although the commission heard about rather lax disciplinary controls by the two key financial planning groups, the Financial Planning Association of Australia and the Association of Financial Advisers.

There is another less well-known group called the Independent Financial Advisers Association of Australia (IFAAA). Members are not allowed to have any ownership links or affiliations with product manufacturers. Nor can they receive commissions or incentive payments from product manufactures.

Asset-based fees are also out. These are fees based on a percentage of a client’s assets under management. ASIC does not view asset-based fees as a conflict of interest but IFAAA says they are commissions by another name. “If you remove the conflict of interest from the table, an enormous amount of heavy lifting is done for you,” IFAAA president Daniel Brammall says. “All that’s left to do is the right thing.”